As a parent, by the time you have your second or third child, you know which battles to fight and which to avoid. It’s time we did the same in business intelligence (BI). For almost two decades we’ve tried to shoehorn both casual users and power users into the same BI architecture. But the two don’t play nicely together. Given advances in technology and the explosion in data volumes and types, it’s time we separate them and create dual BI architectures.

Mapping Architectures

Casual users are executives, managers, and front-line workers who periodically consume information created by others. They monitor daily or weekly reports and occasionally dig deeper to analyze an issue or get details. Generally, a well-designed interactive dashboard or parameterized report backed by a data warehouse with a well-designed dimensional schema is sufficient to meet these information needs. Business users who want to go a step further and build ad hoc views or reports for themselves and peers—whom I call Super Users—are best served with a semantic layer running against the same data warehouse.

Power users, on the other hand, explore data to answer unanticipated questions and issues. No predefined dashboard, report, or semantic layer is sufficient to meet their needs. They need to access data both in the data warehouse and outside of it, beyond the easy reach of most BI tools and predefined metrics and entities. They then need to dump the data into an analytical tool (e.g. Excel, SAS) so they can merge and model the data in novel and unique ways.

For years, we’ve tried to reconcile casual users and power users within the same BI architecture, but it’s a losing cause. Power users generate “runaway” queries that bog down performance in the data warehouse, and they generate hundreds or thousands of reports that overwhelm casual users. As a result, casual users reject self-service BI and revert back to old habits of requesting custom reports from IT or relying on gut feel. Meanwhile, power users exploit BI tools to proliferate spreadmarts and renegade data marts that undermine enterprise information consistency while racking up millions in hidden costs.

Time for a New Analytic Sandbox

Some forward-looking BI teams are now creating a separate analytic architecture to meet the needs of their most extreme power users. And they are relegating their data warehouses and BI tools to handle standard reporting, monitoring, and lightweight analysis.

Compared to a traditional data warehousing environment, an analytic architecture is much more free-form with fewer rules of engagement. Data does not need rigorous cleaning, mapping, or modeling, and hardcore business analysts don’t need semantic guardrails to access the data. In an analytic architecture, the onus is on the business analyst to understand source data, apply appropriate filters, and make sense of the output. Certainly, it is a “buyer beware” environment. As such, there may only be a handful of analysts in your company who are capable of using this architecture. But the insights they generate may make the endeavor well worth the effort and expense.

Types of Analytic Architectures

There are many ways to build an analytic architecture. Below are three approaches. Some BI teams implement one approach; others mix all three.

Physical Sandbox. One type of analytic architecture is uses a new analytic platform—a data warehousing appliance, columnar database, or massively parallel processing (MPP) database—to create a separate physical sandbox for their hardcore business analysts and analytical modelers. They offload complex queries from the data warehouse to these turbocharged analytical environments , and they enable analysts to upload personal or external data to those systems. This safeguards the data warehouse from runaway queries and liberates business analysts to explore large volumes of heterogeneous data without limit in a centrally managed information environment.

Virtual Sandbox. Another approach is to implement virtual sandboxes inside the data warehouse using workload management utilities. Business analysts can upload their own data to these virtual partitions, mix it with corporate data, and run complex SQL queries with impunity. These virtual sandboxes require delicate handling to keep the two populations (casual and power users) from encroaching on each other’s processing territories. But compared to a physical sandbox, it avoids having to replicate and distribute corporate data to a secondary environment that runs on a non-standard platform.

Desktop Sandboxes. Other BI teams are more courageous (or desperate) and have decided to give their hardcore analysts powerful, in-memory, desktop databases (e.g., Microsoft PowerPivot, Lyzasoft, QlikTech,Tableau, or Spotfire) into which they can download data sets from the data warehouse and other sources to explore the data at the speed of thought. Analysts get a high degree of local control and fast performance but give up data scalability compared to the other two approaches. The challenge here is preventing analysts from publishing the results of their analyses in an ad hoc manner that undermines information consistency for the enterprise.

Dual, Not Dueling Architectures

As an industry, it’s time we acknowledge the obvious: our traditional data warehousing architectures are excellent for managing reports and dashboards against standard corporate data, but they are suboptimal for managing ad hoc requests against heterogeneous data. We need dual BI architectures: one geared to casual users that supports standard, interactive reports and dashboards and lightweight analyses; and another tailored to hardcore business analysts that supports complex queries against large volumes of data.

Dual architectures does not mean dueling architectures. The two environments are complementary, not conflicting. Although companies will need to invest additional time, money, and people to manage both environments, the payoff is worth the investment: companies will get higher rates of BI usage among casual users and more game-changing insights from hardcore power users.

0 comments

Every once in a while, you encounter a breath of fresh air in the business intelligence field. Someone who approaches the field with a fresh set of eyes, a barrel full of common sense, and the courage to do things differently. We were fortunate at TDWI’s BI Executive Summit this August in San Diego to have several speakers who fit this mold.

One was Ken Rudin, general manager of analytics and social networking products, at Zynga, the online gaming company that produces Farmville and Mafia Wars, among others. Ken discussed how Zynga is “an analytics company masquerading as an online gaming company.”

Centralized High Priests

One of the many interesting things he addressed was how he reorganized his team from a centralized “high priest” model to a distributed “embedded” model. When he arrived at Zynga, studio heads or project managers would submit requests for analytical work to the corporate analytics team. According to Ken, this approach led business people to view analytics as external or separate from what they do, as something delivered by experts whose time needed to be scheduled and prioritized. In other words, they didn’t view analytics as integral to their jobs. It was someone else’s responsibility.

Another downside of the centralized model (although Ken didn’t mention this) is that analysts become less efficient. Since they are asked to analyze issues from a variety of departments, it takes them more time to get up to speed with germane business and technical issues. As a result, they can easily miss key issues or nuances that lead to below par results. Moreover, analysts serving in a “high priest” approach often feel like “short order cooks” who take requests in a reactive manner and don’t feel very engaged in the process.

Embedding Analysts

To improve the effectiveness of his analytical team, Rudin “gave away” his headcount to department heads. He said he had to go “hat in hand” and ask department heads to assume funding of his analysts. He thought the department heads would push back, but the opposite occurred: the department heads were thrilled to have analysts dedicated to their teams, and even agreed to fund more hires than Rudin proposed.

Embedding analysts in the departments helped cultivate a culture of analytics at Zynga. Each analyst became part of the team involved in designing the games. Their role was to suggest ways to test new new ideas and examine assumptions about what drives retention and longevity. By providing scientific proof of what works or doesn’t work, the embedded model created a perfect blend of “art and science” that has helped fuel Zynga’s extraordinary growth. “Art without science doesn’t work, says Rudin.

To maintain the cohesiveness of an analytical team that doesn’t report to him, Rudin holds 30 minute scrums where all analysts meet daily to share what they’ve learned and develop ideas about approaches, metrics, or tests that might apply across departments. Rudin also maintains two senior analysts who perform cross-departmental analyses.

Rudin had other gems in his presentation so stay tuned for analytical insights in this blog.

0 comments

Here’s a marriage made in heaven: combine search and business intelligence (BI) to create an easy-to-use query environment that enables even the most technophobic business users to find or explore any type of information. In other words, imagine Google for BI.

Search offers some compelling features that BI lacks: it has a brain-dead easy interface for querying information (i.e. the keyword search box made famous by Google and Yahoo); it returns results from a vast number of systems in seconds; and it can pull data from unstructured data sources, such as Web pages, documents, and email.

Of course, search lacks some key features required by BI users: namely, the ability to query structured databases, aggregate and visualize records in tabular or graph form, and apply complex calculations to base-level data. But imagine if you could build a system that delivers the best of both search and BI without any of the downsides?

Given the potential of such a union, a variety of vendors have been working for years to consummate the relationship. Some are search vendors seeking to penetrate the BI market; others are BI vendors looking to make good on the promise of self-service BI; and others are entrepreneurs who believe linguistic technology can bridge the gap between search and SQL.

Here are three approaches vendors are taking to blend search and BI technologies.

1. Faceted BI Search

Faceted BI search—for lack of a better term—is a pureplay integration of search and BI technologies. Information Builder’s Magnify is perhaps the best example of this approach, although Google has teamed up with several BI vendors to offer a search-like interface to structured data sources.

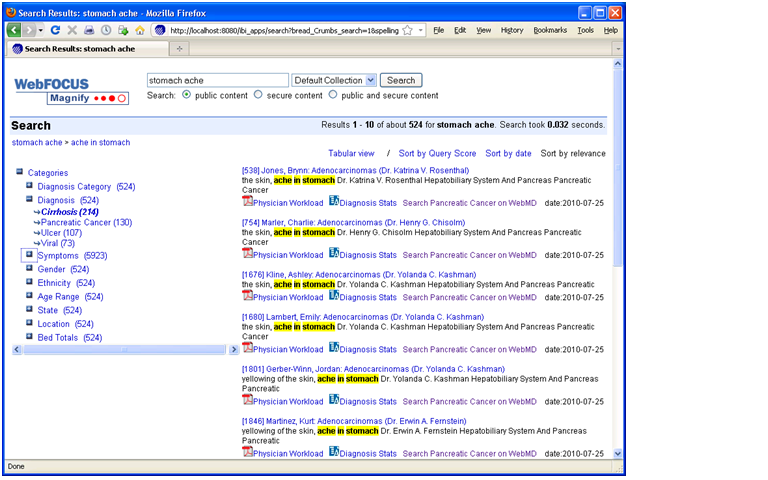

Here, a search engine indexes metadata and data generated by an ETL or reporting tool. When users type a word into the keyword search box, they receive a list of search results in the main body of the page and “facets” (i.e. categories of topics derived from metadata) in the left-hand column (see figure 1.) The results contain links to records in the source systems and reports that are executed on the fly using parameters from the search metadata. Users can also click on the facets to view subcategories and refine their search. Each time they click on a category or subcategory, a new set of result entries appear in the main body of the page.

Figure 1. Faceted Search

Information Builder, Inc.’s WebFocus Magnify is a BI Search product that indexes metadata and data generated by IBI’s ETL tool. The tool’s search engine displays search results in the main body of the page and dynamically generated “facets” or categories in the left-column. The search results contain links to reports that are dynamically generated based on search metadata. Source: Information Builders.

Prior to Faceted BI Search, comparable tools only indexed a BI vendor’s proprietary report files. So you could search for prerun reports in a specific format but nothing else. In contrast, Faceted BI Search dynamically generates reports based on search parameters. Furthermore, those reports can be interactive and parameterized, enabling users to continue exploring data until they find what they are looking for. In this dynamic, search becomes a precursor to reporting which facilitates exploration and analysis. So, the end user process flow is: searchàreportàexplore.

In addition, compared to prior generations of BI Search, Faceted Search indexes any content defined in metadata and fed to the search engine, including relational data, hierarchical data, documents, Web pages, and real-time events streaming across a messaging backbone. As such, the tools serve as surrogate data integration tools since they can mingle results multiple systems, including structured and unstructured data sources. It’s for this reason that in the past I’ve called Faceted Search a “poor man’s data integration tool.”

2. NLP Search

A more sophisticated approach to marrying search and BI involves natural language processing (NLP). NLP uses linguistic technology to enable a computer to extract meaning from words or phrases, such as those typed into a keyword search box. NLP breaks down the sentence structure, interprets the grammar and phrases, deciphers synonyms and parts-of-speech elements, and even resolves misspellings on the fly.

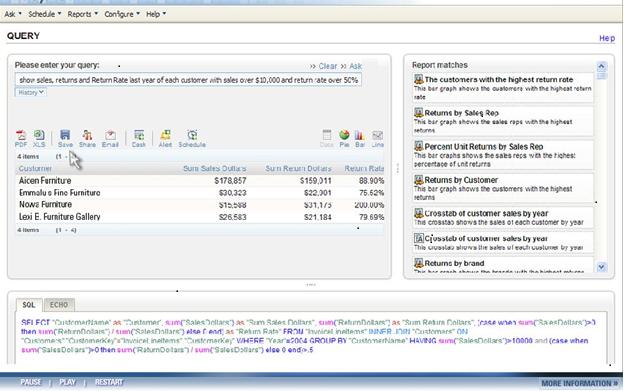

From there, the technology maps the meaning derived from keywords to metadata that describes the content of a database or document. Once this mapping occurs, the tools generate SQL queries against a database schema. All this happens instantaneously, so users can iteratively query a database using plain English rather than SQL or a complex query tool. (See figure 2.)

Figure 2. NLP Search

When users type a query in plain English into an NLP search box, the system suggests related reports (right pane) and hints (not shown) to refine the search. The system then maps the words to underlying database schema and generates SQL (bottom pane) which return the results (left pane), which can then be converted into a table, chart, or dashboard. Source: EasyAsk.

To make the translation between English words and phrases to SQL, the tools leverage a knowledgebase of concepts, business rules, jargon, acronyms, etc. that are germane to any business field. Most NLP tools come with knowledgebase for specific domains, including functional areas and vertical industries. Typically, NLP Search customers need to expand the knowledgebase with their own particular jargon and rules to ensure the NLP tools can translate words into SQL accurately. Often, customers must “train” a NLP Search tool on a specific database that it is going to query to maximize alignment.

While NLP tools may be a tad fussy to train and manage, they come closest to enabling users to query structured data sources. Ironically, despite their linguistic capabilities, the tools usually don’t query unstructured data sources since they are designed to generate SQL. Perhaps this limitation is one reason why pioneers in this space, EasyAsk and Semantra, have yet to gain widespread adoption.

3. Visual Search

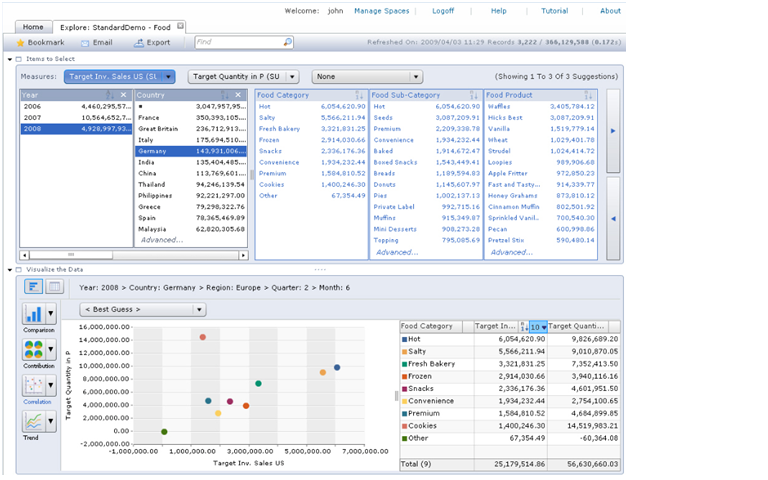

The third approach doesn’t use search technology per se; rather, it mimics the effects of search using advanced BI tools. This type of BI Search runs a visualization tool directly against an analytic platform, usually an in-memory, columnar database with an inverted index that offers blindingly fast query performance. The combination of visualization and in-memory database tools enables users to explore sizable volumes at the speed of thought. Using a point and click paradigm, users can sort, filter, group, drill, and visual data. (See figure 3.)

Figure 3. Visual Search

SAP BusinessObjects Explorer Accelerated marries a visualization tool with an analytic appliance (i.e., in-memory columnar database on an MPP machine) that enables users to “search” large volumes of data in an iterative manner. A user begins by typing a phrase into the keyword search box atop, which is used only to define the “information space” (i.e., the star schema) whose data will be exposed through the visual interface. Source: SAP.

Compared to Faceted BI search, which we described earlier, this approach eliminates the intermediate step of delivering individual search results or entries to users who then have to scan the entries to find one that is relevant and then click on a link to a related report. Instead, Visual Search links data directly to a visual analysis tool, giving users direct access to the information they are looking for along with the ability to dynamically interact with the data.

SAP BusinessObjects Explorer (and the recently announced Explorer Accelerated) and Endeca’s Information Access Platform are examples of Visual Search. While SAP BusinessObjects Explorer runs against star schema databases (primarily SAP BW InfoCubes today but heterogeneous databases in the near future), Endeca runs against both structured and unstructured data sources, which befits is origins as a search applications vendor.

Conclusion

BI Search is bound to gain traction in the BI market because it meets an unmet need: the ability to give casual users (i.e., executives, managers, and front-line workers) an ad hoc query tool that is simple enough to use without training.

Today, most self-service BI tools are too hard to use. And although a well-designed performance dashboard should meet 60% to 80% of the information needs of casual users, they don’t suffice for the other 20% to 40% of occasions when casual users need true ad hoc access to various information sources. Blending the best of search and BI technologies, BI search tools will fill this void.

Posted by Wayne Eckerson0 comments

It used to be that a semantic layer was the sine qua non of a sophisticated BI deployment and program. Today, I’m not so sure.

A semantic layer is a set of predefined business objects that represent corporate data in a form that is accessible to business users. These business objects, such as metrics, dimensions, and attributes, shield users from the data complexity of schema, tables, and columns in one or more back-end databases. But a semantic layer takes time to build and slows down deployment of an initial BI solution. Business Objects (now part of SAP) took its name from this notion of a semantic layer, which was the company’s chief differentiator at its inception in the early 1990s.

A semantic layer is critical for supporting ad hoc queries by non-IT professionals. As such, it’s a vital part of supporting self-service BI, which is all the rage today. So what’s my beef? Well, 80% of most BI users don’t need to create ad hoc queries. The self-service requirements of “casual users” are easily fulfilled using parameterized reports or interactive dashboards which do not require semantic layers to build or deploy.

Accordingly, most pureplay dashboard vendors don’t incorporate a semantic layer. Corda, iDashboards, Dundas, and others are fairly quick to install and deploy precisely because they have a lightweight architecture (i.e., no semantic layer). Granted, most are best used for departmental rather than enterprise deployments, but nonetheless, these low-cost, agile solutions often support sophisticated BI solutions.

Besides casual users, there are “power users” who constitute about 20% of total users. Most power users are business analysts who typically query a range of databases, including external sources. From my experience, most bonafide analysts feel constrained by a semantic layer, preferring to use SQL to examine and extract source data directly.

So is there a role for a semantic layer today? Yes, but not in the traditional sense of providing “BI to the masses” via ad hoc query and reporting tools. Since the “masses” don’t need such tools, the question becomes who does?

Super Users. The most important reason to build a semantic layer is to support a network of “super users.” Super users are technically savvy business people in each department who gravitate to BI tools and wind up building ad hoc reports on behalf of colleagues. Since super users aren’t IT professionals with formal SQL training, they need more assistance and guiderails than a typical application developer. A semantic layer ensures super users conform to standard data definitions and create accurate reports that align with enterprise standards.

Federation. Another reason a semantic layer might be warranted is when you have a federated BI architecture where power users regularly query the same sets of data from multiple sources to support a specific application. For example, a product analyst may query historical data from a warehouse, current data from sales and inventory applications, and market data from a syndicated data feed. If this usage is consistent, then the value of building a semantic layer outweighs its costs.

Distributed Development. Mature BI teams often get to the point where they become the bottleneck for development. To alleviate the backlog of projects, they distribute development tasks back out to IT professionals in each department who are capable of building data marts and complex reports and dashboards. To make distributed development work, the corporate BI team needs to establish standards for data and metric definitions, operational procedures, software development, project management, and technology. A semantic layer ensures that all developers use the same definitions for enterprise metrics, dimensions, and other business objects.

Semi-legitimate Power Users. You have inexperienced power users who don’t know how to form proper SQL and aren’t very familiar with the source systems they want to access. This type of power user is probably more akin to a super user than a business analyst and would be a good candidate for a semantic layer. However, before outfitting these users with ad hoc query tools, first determine whether a parameterized report, an interactive dashboard, or a visual analysis tool (e.g., Tableau) can meet their needs.

So there you have it. Semantic layers facilitate ad hoc query and reporting. But the only people who need ad hoc query and reporting tools these days are super users and distributed IT developers. However, if you are trying to deliver BI to the masses of casual users, then a semantic layer might not be worth the effort. Do you agree?

Posted by Wayne Eckerson0 comments

Designing dashboards is not unlike decorating a room in your house. Most homeowners design as they purchase objects to place in the room. When we buy a rug, we select the nicest rug; when we pick out wall paint, we pick the most appealing color; when we select chairs and tables, we find the most elegant ones we can afford. Although each individual selection makes sense, collectively the objects clash or compete for attention.

Smart homeowners (with enough cash) hire interior decorators who filter your tastes and preferences through principles of interior design to create a look and feel in which every element works together harmoniously and emphasizes what really matters. For example, the design might highlight an elegant antique coffee table by selecting carpets, couches, and curtains that complement its color and texture.

To optimize the design of your performance dashboard, it is important to get somebody on the team who is trained in the visual design of quantitative information displays. Although few teams can afford to hire someone full time, you may be able to hire a consultant to provide initial guidance or find someone in the marketing department with appropriate training. Ideally, the person can educate the team about basic design principles and provide feedback on initial displays.

But be careful: don’t entrust the design to someone who is a run-of-the-mill graphic artist or who is not familiar with user requirements, business processes, and corporate data. For example, a Web designer will give you a professional looking display but will probably garble the data—they might use the wrong type of chart to display data or group metrics in nonsensical ways or apply the wrong filters for different user roles. And any designer needs to take the time upfront to understand user requirements and the nature of the data that will populate the displays.

Ideally, report developers and design experts work together to create an effective series of dashboard displays, complementing their knowledge and expertise. This partnership can serve as a professional bulwark against the sometimes misguided wishes of business users. Although it’s important to listen to and incorporate user preferences, ultimately the look and feel of a dashboard should remain in the hands of design professionals. For example, most companies today entrust the design of their Web sites and marketing collateral to professional media designers who work in concert with members of the marketing team. They don’t let the CEO dictate the Web design (or shouldn’t anyway!)

There are many good books available today to help dashboard teams bone up on visual design techniques. The upcoming second edition of my book, “Performance Dashboards: Measuring, Monitoring, and Managing Your Business” has a chapter devoted to visual design techniques. Many of the concepts in the chapter are inspired by Stephen Few whose “Information Dashboard Design” book is a must read. Few and others have drawn inspiration from Edward R. Tufte, whose book, “The Visual Display of Quantitative Information,” is considered a classic in the field. Tufte has also written “Visual Explanations,” “Envisioning Information” and “Beautiful Evidence.”

Posted by Wayne Eckerson0 comments

(Caution: This blog may contain ideas that are hazardous to your career.)

I’ve argued in previous blogs that business intelligence (BI) professionals must think more like business people and less like IT managers if they are to succeed. However, while many BI professionals have their hearts in the right place, their actions speak differently. They know what they need to do but can’t seem to extricate themselves from an IT mindset. That takes revolutionary thinking and a little bit of luck.

Radical Thinking

So, here’s a radical idea that will help you escape the cultural bonds of IT: don’t upgrade your BI software.

Now, if you gasped after reading that statement, you’re still an IT person at heart. An IT person always believes in the value of new software features and fears losing vendor support and leverage by not staying fairly current with software licenses and versions.

Conversely, the average business person sees upgrades as a waste of time and money. Most don’t care about the new functionality or appreciate the financial rationale or architectural implications. To them, the upgrade is just more “IT busywork.”

Here’s another radical idea: stick with the BI tools you have. Why spend a lot of money and time migrating to new platform when the one you have works? So what if the tools are substandard and missing features? Is it really a problem if the tools force your team to work overtime to make ends meet? Who are the tools really designed to support: you or the users?

In the end, it’s not the tools that matter, it’s how you apply them. Case in point: in high school, I played clarinet in the band. One day, I complained vociferously to the first chair, a geeky guy named Igor Kavinsky who had an expensive, wooden clarinet (which I coveted), that my cheap, plasticized version wasn’t working very well and I needed a replacement. Before I could list my specific complaints, he grabbed my clarinet, replaced the mouthpiece, and began playing.

Lo and behold, the sound that came from my clarinet was beautiful, like nothing I had ever produced! I was both flabbergasted and humiliated. It was then I realized that the problem with my clarinet not the instrument but me! Igor showed me that it’s the skill of the practitioner, not the technology, that makes all the difference.

Reality Creeps In

Igor not withstanding, if you’re a good, well-trained IT person, you probably think my prior suggestions are unrealistic, if not ludicrous. In the “real world,” you say, there is no alternative to upgrading and migrating software from time to time. These changes—although painful—improve your team’s ability to respond quickly to new business needs and avoid a maintenance nightmare. And besides, many users want the new features and tools, you insist.

And of course, you are right. You have no choice.

Yet, given the rate of technology obsolescence and vendor consolidation, your team probably spends 50% of its time upgrading and migrating software. And it spends its remaining time maintaining both new and old versions (because everyone knows that old applications never die.) All this busywork leaves your team with precious little time and resources to devise new ways to add real value to the business.

Am I wrong? Is this a good use of your organization’s precious capital? What would a business person think about the ratio of maintenance to development dollars in your budget?

Blame the Vendors. It’s easy to blame software vendors for this predicament. In their quest for perpetual growth and profits, vendors continually sunset existing products, forcing you (the hapless customer) with no choice but to upgrade or lose support and critical features. And just when you’ve fully installed their products, they merge with another company and reinvent their product line, forcing another painful migration. It’s tempting to think that these mergers and acquisitions are simply diabolical schemes by vendors to sell customers expensive, replacement products. Just ask any SAP BI customer!

Breaking the Cycle

If this describes your situation, what do you do about it? How do you stop thinking like an IT person and being an IT cuckold to software vendors?

Most BI professionals are burrowed more deeply in an IT culture than they know. Breaking free often requires a cataclysmic event that rattles their cages and creates an opening to escape. This might be a change in leadership, deregulation, a new competitor, or a new computing platform. Savvy BI managers seize such opportunities to reinvent themselves and change the rules of the game.

Clouds Coming. Lucky for you, the Cloud—or more specifically, Software as a Service (SaaS)—is one of those cataclysmic events. The Cloud has the potential to liberate you and your team from an overwrought IT culture that is mired in endless, expensive upgrades and painful product migrations, among other things.

The beauty of a multi-tenant, cloud-based solution is that you never have to upgrade software again. In a SaaS environment, the upgrades happen automatically. To business and IT people, this is magical: cool new features appear and no one had to do any work or suffer any inconvenience. SaaS also eliminates vendor lock in since you can easily change cloud vendors (as long as you maintain your data) by just pointing users to a new URL. The Cloud is a radical invention that promises to alter IT culture forever.

Getting Started. To break the cycle, start experimenting with cloud-based BI solutions. Learn how these tools work and who offers them. Use the cloud for prototypes or small, new projects. Some cloud BI vendors offer a 30-day free trial while more scalable solutions promise to get you up and running quickly. If you have a sizable data warehouse, leave your data on premise and simply point the cloud BI tools to it. Performance won’t suffer.

Unless you experiment with ways to break free from an IT culture, you never will. Seize the opportunity that the Cloud affords and others that are sure to follow. Carpe diem!

Posted by Wayne Eckerson0 comments

Data federation is not a new technique. The notion of virtualizing multiple back-end data sources has been around for a long time, reemerging every decade or so with a new name and mission.

Database Gateways. In the 1980s, database vendors introduced database gateways that transparently query multiple databases on the fly, making it easier for application developers to build transaction applications in a heterogeneous database environment. Oracle and IBM still sell these types of gateways.

VDW. In the 1990s, vendors applied data federation to the nascent field of data warehousing, touting its ability to create “virtual” data warehouses. However, data warehousing purists labeled the VDW technology as “voodoo and witchcraft” and it never caught on, largely because standardizing disparate data from legacy systems was nearly impossible to do without creating a dedicated data store.

EII. By the early 2000’s, with more powerful computing resources, data federation was positioned as a general purpose data integration tool, adopting the moniker “enterprise information integration” or EII. The three-letter acronym was designed to mirror ETL—extract, transform, and load—which had become the predominant method for integrating data in data warehouses.

Data Services. In addition, the rise of Web services and services oriented architectures during the past decade gave data federation another opportunity. It got positioned as a data service, abstracting back-end data sources behind a single query interface. It is now being adopted by many companies that are implementing services oriented architectures.

Data Virtualization. Today, data federation vendors now prefer the label of data virtualization, capitalizing on the popularity of hardware virtualization in corporate data centers and the cloud. The term data virtualization reinforces the idea that data federation tools abstract databases and data systems behind a common interface.

Data Integration Toolbox

Over the years, data federation has gained a solid foothold as an important tool in any data integration toolbox. Companies use the technology in a variety of situations that require unified access to data in multiple systems via high-performance distributed queries. This includes data warehousing, reporting, dashboards, mashups, portals, master data management, SOA architectures, post- acquisition systems integration, and cloud computing.

One of the most common uses of data federation are for augmenting data warehouses with current data in operational systems. In other words, data federation enables companies to “real-time-enable” their data warehouses without rearchitecting them. Another common use case is to support “emergency” applications that need to be deployed quickly and where the organization doesn’t have time or money to build a data warehouse or data mart. Finally, data federation is often used to create operational reports that require data from multiple systems.

A decade ago there were several pureplay data federation vendors, but now the only independent is Composite Software, which is OEM’d by several BI vendors, including IBM Cognos. Other BI vendors support data federation natively, including Oracle (OBIEE) and MicroStrategy. And many data integration vendors, including Informatica and SAP have added data federation to their data integration portfolios.

Federation versus Integration

Traditionally, the pros and cons of data federation are weighed against those of data integration toolsets, especially when creating data warehouses. The question has always been “Is it better to build virtual data warehouses with federation tools or physical data marts and data warehouses with ETL tools?”

Data federation offers many advantages -- it’s a fast, flexible, low cost way to integrate diverse data sets in real time. But data integration offers benefits that data federation doesn’t: scalability, complex transformations, and data quality and data cleansing.

But what if you could combine the best of these two worlds and deliver a data integration platform that offered data federation as an integrated module, not a bolt on product? What if you could get all the advantages of both data federation and data integration in a single toolset?

If you could have your cake and eat it, too, you might be able to apply ETL and data quality transformations to real-time data obtained through federation tools. You wouldn’t have to create two separate semantic models, one for data federation and another ETL; you could use one model to represent both modalities. Basically, you would have one tool instead of two tools. This would make it easier, quicker, and cheaper to apply both data federation and data integration capabilities to any data challenge you might encounter.

This seamless combination is the goal of some data integration vendors. I recently did a Webcast with Informatica, which shipped a native data federation capability this year that runs on the same platform as its ETL tools. This is certainly a step forward for data integration teams that want a single, multipurpose environment instead of multiple, independent tools, each with their own architecture, metadata, semantic model, and functionality.

Posted by Wayne Eckerson0 comments

People think analytics is about getting the right answers. In truth, it’s about asking the right questions.

Analysts can find the answer to just about any question. So, the difference between a good analyst and a mediocre one is the questions they choose to ask. The best questions test long-held assumptions about what makes the business tick. The answers to these questions drive concrete changes to processes, resulting in lower costs, higher revenue, or better customer service.

Often, the obvious metrics don’t correlate with sought-after results, so it’s a waste of time focusing on them, says Ken Rudin, general manager of analytics at Zynga and a keynote speaker at TDWI’s upcoming BI Executive Summit in San Diego on August 16-18.

Challenge Assumptions

For instance, many companies evaluate the effectiveness of their Web sites by calculating the number of page hits. Although a standard Web metric, total page hits often doesn’t correlate with higher profits, revenues, registrations, or other business objectives. So, it’s important to dig deeper, to challenge assumptions rather than take them at face value. For example, a better Web metric might be the number of hits that come from referral sites (versus search engines) or time spent on the Web site or time spent on specific pages.

TDWI Example. Here’s another example closer to home. TDWI always mails conference brochures 12 weeks before an event. Why? No one really knows; that’s how it’s always been done. Ideally, we should conduct periodic experiments. Before one event, we should send a small set of brochures 11 weeks beforehand and another small set 13 weeks prior. And while we’re at it, we should test the impact of direct mail versus electronic delivery on response rates.

These types of analyses don’t take sophisticated mathematical software and expensive analysts; just time, effort, and a willingness to challenge long-held assumptions. And the results are always worth the effort; they can either validate or radically alter the way we think our business operates. Either way, the information impels us to fine-tune or restructure core business processes that can lead to better bottom-line results.

Analysts are typically bright people with strong statistical skills who are good at crunching numbers. Yet, the real intelligence required for analytics is a strong dose of common sense combined with a fearlessness to challenge long-held assumptions. “The key to analytics is not getting the right answers,” says Rudin. “It’s asking the right questions.”

Posted by Wayne Eckerson0 comments

Business analysts are a key resource for creating an agile organization. These MBA- or PhD-accredited, number-crunchers can quickly unearth insights and correlations so executives can make critical decisions. Yet, one decision that executives haven’t analyzed thoroughly is the best way to organize business analysts to enhance their productivity and value.

Distributed Versus Centralized

Traditionally, executives either manage business analysts as a centralized, shared service or allow each business unit or department to hire and manage their own business analysts. Ultimately, neither a centralized or distributed approach is optimal.

Distributed Approach. In a distributed approach, a department or business unit head hires the analyst to address local needs and issues. This is ideal for the business head and departmental managers who get immediate and direct access to an analyst. And the presence of one or more analysts helps foster a culture of fact-based decision making. For example, analysts will often suggest analytical methods for testing various ideas, helping managers become accustomed to basing decisions on fact rather than gut feel alone.

However, in the distributed approach, business analysts often become a surrogate data mart for the department. They get bogged down creating low-value, ad hoc reports instead of conducting more strategic analyses. If the business analyst is highly efficient, the department head often doesn’t see the need to invest in a legitimate, enterprise decision-making infrastructure. From an analyst perspective, they often feel pigeonholed in a distributed approach. They see little room for career advancement and few opportunities to expand their knowledge in new areas. They often feel isolated and have few opportunities to exchange ideas and collaborate on projects with fellow analysts. In effect, they are “buried” in departmental silos.

Centralized Approach. In a centralized approach, business analysts are housed centrally and managed as a shared service under the control of a director of analytics, or more likely, a chief financial officer or director of information management. One benefit of this approach is that organizations can assign analysts to strategic, high priority projects rather than tactical, departmental ones, and the director can establish a strong partnership with the data warehousing and IT teams which control access to data, the fuel for business analysts. Also, by being co-located, business analysts can more easily collaborate on projects, mentor new hires, and cross-train in new disciplines. This makes the environment a more rewarding place to work for business analysts and increases their retention rate.

The downside of the centralized approach is that business analysts are a step removed from the people, processes, and data that drive the business. Without firsthand knowledge of these things, business analysts are less effective. It takes them longer to get up to speed on key issues and deliver useful insights, and they may miss various nuances that are critical for delivering a proper assessment. In short, without a close working relationship with the people they support and intimate knowledge of local processes and systems, they are running blind.

Hybrid Approach

A more optimal approach combines elements of both distributed and centralized methods. In a hybrid environment, business analysts are embedded in departments or business units but report directly to a director of analytics. This sounds easy enough, but it’s hard to do. It’s ideal when the company is geographically consolidated in one place so members of the analytics team can easily physically reconvene as a group to share ideas and discuss issues.

Zynga. For example, Zynga, an internet gaming company, uses a hybrid approach for managing its analysts. All of Zynga’s business analysts report to Ken Rudin, director of analytics for the company. However, about 75% of the analysts are embedded in business units, working side by side with product managers to enhance games and retain customers. The remainder sit with Rudin and work on strategic, cross-functional projects. (See “Proactive Analytics That Drive the Business” in my blog for more information on Zynga’s analytics initiative.) This setup helps deliver the best of both centralized and distributed approaches.

Every day, both distributed and centralized analysts come together for a quick “stand up” meeting where they share ideas and discuss issues. This helps preserve the sense of team and fosters a healthy exchange of knowledge among all the analysts, both embedded and centralized. Although Zynga’s analysts all reside on the same physical campus, a geographically distributed team could simulate “stand up” meetings with virtual Web meetings or conference calls.

Center of Excellence. The book “Analytics at Work” by Tom Davenport, Jeanne Harris, and Robert Morison describes five approaches for organizing analysts, most of which are variations on the themes described above. One approach, “Center of Excellence” is similar to the Hybrid approach above. The differences are that all (not just some) business analysts are embedded in business units, and all are members of (and perhaps report dotted line to) a corporate center of excellence for analytics. Here, the Center of Excellence functions more like a program office that coordinates activities of dispersed analysts rather than a singular, cohesive team, as in the case of Zynga.

Either approach works, although Zynga’s makes it easier for an inspired director of analytics to shape and grow the analytics department quickly and foster a culture of analytics throughout the organization.

Summary. As an organization recognizes the value of analytics, it will evolve the way it organizes its business analysts. Typically, companies will start off on one extreme—either centralized or distributed—and then migrate to a more nuanced hybrid approach in which analysts report directly to a director of analytics (i.e., Zynga) or are part of a corporate Center of Excellence.

Posted by Wayne Eckerson0 comments

To create high-performance BI teams, we need to attract the right people. There are a couple of ways to do this.

Skills Versus Qualities

Inner Drive. First, don’t just hire people to fill technical slots. Yes, you should demand a certain level of technical competence. For example, everyone on the award winning BI team at Continental Airlines in 2004 had training as a database administrator. But these days, technical competence is simply a ticket to play the game. To win the game, you need people who are eager to learn, highly adaptable, and passionate about what they do.

The bottom line is that you shouldn’t hire technical specialists whose skills may become obsolete tomorrow if your environment changes. Hire people who have inner drive and can reinvent themselves on a regular basis to meet the future challenges your team will face. If you need pure technical specialists, consider outsourcing or contracting people to fill these roles.

Think Big. To attract the right people, it’s important to set ambitious goals. A big vision and stretch targets will attract ambitious people who seek new challenges and opportunities and discourage risk-adverse folks who simply want a “job” and a company to “take care” of them. One way to think big is to run the BI group like a business. Create mission, vision, and values statements for your team and make sure they align with the strategic objectives of your organization. Put people in leadership positions, delegate decision making, and hold them accountable for results. Reward them handsomely for success (monetarily or otherwise) yet don’t punish failure. View mistakes as “coaching opportunities” to improve future performance or as evidence that the team needs to invest more resources into the process or initiative.

Performance-based Hiring

Proactive Job Descriptions. We spend a lot of time measuring performance after we hire people, but we need to inject performance measures into the hiring process itself. To do this, write proactive job descriptions that contain a mission statement, a series of measurable outcomes, and the requisite skills and experience needed to achieve the outcomes. Make sure the outcomes are concrete and tangible: such as “improve the accuracy of the top dozen data elements to 99%” or “achieve a rating of “high” or better from 75% of users in the annual BI customer satisfaction survey” or “successfully deliver 12 major projects a year on time and in budget.”

If done right, a proactive job description helps prospective team members know exactly what they are getting into. They know specific goals they have to achieve and when they have to achieve them. A proactive job description helps them evaluate honestly whether they have what it takes to do the job. It also becomes the new hire’s performance review and a basis for merit pay. For more information on writing these proactive job descriptions, I recommend reading the book, “Who: A Method for Hiring” by Geoff Smart and Randy Street.

Where are they? So where do you find these self-actuated people? Steve Dine, president of DataSource Consulting and a TDWI faculty member, says he tracks people on Twitter and online forums, such as TDWI’s LinkedIn group. He evaluates them by identifying the number of followers they have and assessing the quality of advice they offer. And he avoids the major job boards, such as Monster.com or Dice.com. A more direct and surefire method is to hire someone on a contract basis to see what kind of work they do and how they get along with others on your team.

Retaining the Right People

Finally, to retain your high-performance team, you need to understand what makes BI professionals tick. Salary is always a key factor, but not the most important one. (See TDWI’s annual Salary, Roles, and Responsibility Report.) Above all else, BI professionals want new challenges and opportunities to expand their knowledge and skills. Most get bored if forced to specialize in one area for too long. It’s best to provide BI professionals with ample opportunity to attend training classes so they can pick up new skills.

One way to retain valuable team members is to create small teams responsible for delivering complete solutions. This gives team members exposure to all technologies and skills needed to meet business needs and also gives them ample face time with the business folks who use the solution. BI professionals are more motivated when they understand how their activities contribute to the organization’s overall success. Another retention technique is to give people opportunities to exercise their leadership skills. For instance, assign your rising stars to lead small, multidisciplinary teams where they define the strategy, execute the plans, and report their progress to the team as a whole.

Summary. By following these simple techniques, you will attract the right people to serve on your team and give them ample opportunity to stay with you. For more information on creating high performance BI teams, see a recent entry at my Wayne’s World blog titled “Strategies for Creating High Performance Teams” and the slide deck by the same title at my LinkedIn Page.

Posted by Wayne Eckerson0 comments